Make no mistake, history does repeat. Just don’t expect an exact replication.

At the dawn of cinema, the Lumière brothers had audiences leaping from their seats when it appeared a train pulling into a station was going to break through the screen and come barreling into the auditorium. (There’s been some pushback about whether this actually happened, but I’m going with the legend.) Two years after Al Jolson’s voice poured from movie screens in The Jazz Singer, Alfred Hitchcock garbled the dialogue of a nosey gossip in Blackmail to give us a view of the world from the perspective of a guilty murderer, who could only discern the damning word, “knife.” Technicolor had already established a foothold in Hollywood, but when Dorothy opened a sepia door into the rainbow world of Oz, the process served a function beyond delivering candy colors to moviegoers.

IMAX and 3D had been decades in existence, but in Gravity, Alfonso Cuarón ganged the technologies to make palpable the near-insurmountable odds against an astronaut stranded in space.

Across the history of film, new technologies are introduced, and filmmakers—by design mostly, and occasionally by accident—discover unique ways to employ these processes to enhance their storytelling.

Virtual reality, VR, has been available in one form or another for close to thirty years. For most of those decades, access has been sporadic—my first taste was in the early ’90s, by paying (I’m working from memory here) a dollar a minute to don a VR visor just slightly larger than the hood of a Chevy Corvair for the sole purpose of blasting friends in a coliseum that looked like a cross between a Hercules movie and Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” video. The technology would come and go—Disney experimented with it at their Florida theme parks; Nintendo would kinda sorta have a go at a consumer-level product, to, shall we say, less than impressive results. (Want to start a war? Mention Virtual Boy to a gamer.)

It wasn’t until 2016, with the official release of the Oculus Rift, that VR made a push for the mainstream. In short order, Sony introduced Playstation VR, HTC the Vive, Google unveiled the down-market, smart-phone-powered, Cardboard and its follow-up, the Daydream, and Samsung joined forces with Oculus to create the Gear VR, a visor that you could snap (only!) your Samsung phone into.

This first wave put up a few barriers to widespread adoption. The Rift, Vive, and Playstation devices required you to be tethered to the computer or gaming system that would actually generate the graphics. And in the Rift’s case, your Best Buy home office junker wasn’t going to cut it—in addition to $599 you’d sunk into the visor, you needed to tack at least another $1000 on for the engine powerful enough to drive the thing. The Playstation buy-in wasn’t as punitive, but in addition to the (often discounted) $399 price for the visor, you still had to invest in a Playstation 4, if you hadn’t done so already. Meanwhile, first-adopters deciding to cheap out with Google’s Cardboard or any number of China-built, eBay-available smart phone headsets got, depending on the size of your phone’s screen, at best something VR-ish, like being immersed in a world you could only perceive through a cardboard tube.

The impediments to mass adoption apparently bugged the folks at Oculus (perhaps goaded on by owner Facebook, whose mantra is clearly, “More subscribers, more sooner”). So last year, the company announced three new units: 2019 would see the release of the next-generation Rift, the Rift S, and the Oculus Quest, a standalone unit that would deliver a fully immersive VR experience while freeing the user from being tied down to a base station, all for the not-nearly-as-insane sum of $399.

But before that, in 2018, there would be the Oculus Go, essentially a souped-up Gear VR with improved optics and a better video screen built into the unit itself. There would be compromises—instead of the impressive, dual-wand controllers of the other units, Go owners would have to make do with single, pistol-like remote and incorporated track pad. And instead of the full six degrees of freedom (6DoF) that allowed Rift and Quest owners to physically wander their VR worlds—within the limits of, y’know, real walls—the Go would have only 3DoF, requiring users to stand or sit (ideally in a swiveling chair) in place as they turned and tilted their glance. It was the difference between turning to look at a box and walking up and leaning over to see what was inside.

But it turned out Go users weren’t surrendering as much as first appeared. Lateral movement would be shunted to the controller, an easy adaptation for anyone who’d spent any time with a mouse or game pad. Meanwhile, this would be a fully immersive VR experience, with respectable graphics power and impressive optics for so modest a system. And there was one more incentive: a purchase price of $199, moving the buy-in from, “One day…” to “I could gift this to myself for Christmas!”

More important for the purpose of our conversation, the Go’s functionality, like the Gear VR before it, would be weighted toward entertainment over gaming. There would still be no shortage of opportunities to engage in space battles, role-playing, shooting zombies, hitting the links, running gauntlets, shooting zombies, solving puzzles, shooting zombies, shooting zombies (soooo many zombies…), but the prime function of the Go would be to deliver—or deliver you to—immersive experiences, with varying levels of interactivity thrown in.

Which was perfect for me. I’m a film journalist and critic first, more interested in how tech can be used to enhance the art of storytelling than in how many zombies I can kill (really, it gets old fast). The price was right, and came the Cyber Monday discounts, I gambled my hard-earned bucks for passage to VR World.

After six-plus months, I have no regrets. Unlike cinematic 3D, which too rarely has managed to justify its deployment in a film—turns out being visually deeper doesn’t mean a tale becomes conceptually deeper—what I’ve discovered in my explorations is that fully immersing the viewer in a world does open new avenues to how one becomes invested in a story, and poses new challenges in how that story is told.

***

(A technical note: The titles that will be discussed below have all been experienced on the Oculus Go. However, they may be available on other platforms and, depending on the sophistication of the equipment, may offer additional features or be lacking features available on the Go. I’ll try to account for all the platforms that offer these titles, but may miss some—there are a lot. Don’t believe me? Check out the KEY: OG = Oculus Go and Gear VR; OR = Oculus Rift; OQ = Oculus Quest; HV = HTC Vive; PS = Playstation VR; ST = Steam VR; GP = Google Play; GD = Google Daydream; AA = Apple App Store; WM = Windows Mixed Reality)

The most exciting thing, for me, about VR is that it remains a very new medium, giving storytellers no shortage of opportunity to test and invent as they spin their tales. Not that you’re morally obligated to—computer animator Tyler Hurd takes an easy route in adapting his original 2D short film into Butts: The VR Experience (2016 – OG; OR; HV), about an ebullient free spirit who rescues a grieving soul through the life-affirming wonder of, uh, butts (it’s funny-raunchy, not raunchy-raunchy—very funny-raunchy, actually). Hurd’s conversion strategy is basically to remove the cuts from the film, telling the tale in one long take. It works… mostly—there are moments in the 2D original when Hurd’s quasi-Ren and Stimpy animation style benefits from a change of camera angle; those impacts are lost when the vantage point is locked at a distance. But there’s a nice moment when Hurd has to handle a transition: Instead of dissolving from one scene to the next, as he does in the 2D version, the director lets a cloud of falling confetti lead the eye down from the closing moments of the first sequence into the next sequence’s opening. It’s a (kind of) organic edit, and for a film about a couple of dudes shooting confetti out of their butts, it’s pretty damn elegant.

If only director Steve Miller had been as conscious of the audience’s glance when he created the CG animated The Great C (2019 – OG; OR; HV; ST; GD). Adapted from the short story by Philip K. Dick, albeit loosely (is there any other kind of Phil Dick adaptation?), this story of a young member of a post-apocalyptic tribe sent to pay obeisance to the computer that now rules the Earth offers nicely developed environments, good character animation, and a story that, even as it blithely ignores Dick’s original intent, is still pretty compelling. Where Miller slips up is in not completely thinking through the difference in shooting for a 360° world as opposed to framing for a standard film—the old rules don’t always apply. For example, in traditional film, when a character looks past the camera, it makes perfect sense to cut to a reverse angle to show whatever she/he may be looking at. But in VR, instinct is very likely to compel a viewer to just turn around to find out what’s so freakin’ interesting over her/his shoulder. Bad timing, then, to cut right at that moment, as Miller is wont to do. You want to help your viewer remain oriented in your world—too many “Wait, where the hell am I?” moments can only undercut a story.

Director Adam Cosco has better insight into where an audience’s eyes may be, and how to get them to where they’re next needed. Largely eschewing an omnipotent viewpoint for his live-action, Twilight Zone-ish film, Knives (2016—available on the Dark Corners app—OG; OR; GP; GD; AA), he brings his camera in close to the woman who suspects her husband is cheating on her—and the knife salesman who approaches her with an, ahem, “special” offer—holds for a time sufficient for us to appreciate the interactions (sometimes even dropping the camera down between two characters) and makes sure our eyes are set up for the cut to the next shot. The approach doesn’t always lead to rewards—a wrong turn at one point will face-plant you square into the crotch of a cadaver—and occasionally Cosco’s VR rig will literally show its seams. But with evocative, (mostly) black and white photography and a clever script, the film delivers its shivers with a singular brand of intimacy.

Syfy, in conjunction with Digital Domain, tries to forge its own trail with the CG animated Eleven Eleven (2019 – OG; OR; PS; HV; ST; AA). Set real-time in the last eleven minutes and eleven seconds before an evil corporation unleashes worldwide genocide on a planet’s population, the film allows you to follow six different characters over the same timeline, your insight into their situations deepening as their paths cross. While the experience becomes richer the more you relive the scenario, it remains unclear what virtual reality brings to the table—it’s as if Syfy took a look at Dark Mirror‘s “Bandersnatch” and said, “Okay, we see your branching timelines and raise you VR.” The app does allow you to switch between viewpoints mid-story, watch over the entire location from a so-called “Goddess Mode,” and—on more sophisticated equipment—give you some freedom to roam around the story’s locations. None of this adds anything appreciable to the narrative.

Probably the highest profile name to dip a toe into the VR pool is Robert Rodriguez, not surprising given his overall techy bent—anybody remember Spy Kids 3D? (Or, more to the point, who’s still trying to forget Spy Kids 3D?) His live-action The Limit (2018 – OG; OR; PS; HV; ST; GP; GD; AA; WM) avails itself of something called the STX Surreal Theater to tell its tale of two kickass cyborg agents—one is you, the other is played by Michelle Rodriguez—tracking down a rogue operative (or something, it really doesn’t matter) played by Norman Reedus. This boils down to an immersive, 180° 3D view, as if you were watching within a dome set on its side (turn too far to the left or right, and you find you’re sitting in a rather luxe screening room—VR in general is full of video playback apps set in either luxe screening rooms or, for some reason, ski chalets).

This is one of Rodriguez’s homebrew, family affair exercises—his son, Racer Max, co-wrote, while sibling Rebel handles the score—and the low-budget shows, which is not completely without its charms. And while restricting the VR to front-and-center feels like a little bit of a cheat, Rodriguez is so clearly getting off on applying his well-seasoned action hand and humor to this new format—how can you not love Michelle Rodriguez casually handing you a staple gun to mend your wounds?—that he can be forgiven for not wanting to shoot the stuff you’re not going to be looking at. The Limit is allegedly the first part of an ongoing story, but to be blunt, VR is full of first chapters that never receive a second, much less a third or fourth, installment. Maybe, if Rodriguez does decide to go forward, he’ll feel emboldened to see what happens when he expands his canvas to a full 360°. At the very least, he should check to see if anyone at distributor STX knows the actual meaning of the word “surreal.”

Rodriguez has no reluctance about exploiting a technology for its full, sensual value. Neither, to a great extent, do Chinese filmmakers. While the Western approach to traditional, 3D filmmaking has pretty much resolved to, “We’re a fully mature technology now, we no longer need to indulge in such infantile foolishness as throwing stuff at the audience,” Chinese filmmakers go, “Throwing stuff at the audience? Count us in!” Fists, demons, and all forms of bric-a-brac get flung at you with wild abandon and, at times, without consideration for the welfare of the spectator—the only time I’ve ever suffered motion sickness while watching 3D was at a screening of Young Detective Dee: Rise of the Sea Dragon.

So it’s no surprise that CG directors Mi Li and Wang Zheng’s Shennong: Taste of Illusion (2019 – available on the VeeR app—OG; OR; HV; GD; WM) goes stops-out in deploying every trick in the VR book. Not that you’re immediately flung into the maelstrom—the filmmakers know enough to gradually build up their tale of how a wandering (and horned) god-king of medicine eats the wrong flower and ends up in a hallucinogenic battle with a raging monster. Playing the protagonist first for laughs (with some charming character animation), the filmmakers progressively remodel him as full-on action hero, while taking the surroundings to increasing levels of stylization, from a frosted-over river bank to stark white and black pen-and-ink voids that allow for mind-bending confusions of foreground and background. It does seem to take a while for the filmmakers to adjust to their immersive environs—I’m not sure why they thought it’d be a good idea to start their story with the audience facing 180° in the wrong direction—but by the time they unleash a final face-off between god and monster on glowing, spinning disks of volcanic rock, they’ve created such a whirlwind spectacle of Tsui Hark-caliber action that one is willing to let a few initial stumbles slide.

No less surreal (there, that’s how you use that word), though considerably more restrained, is Gilles Freissinier’s interactive, CG animated S•E•N•S (2016 – OG; OR; GP; AA). Based on the graphic novel by French artist Marc-Antoine Mathieu, this three-chapter, narrative-free experience takes SHENNONG’s confusions of foreground and background and amplifies the concept to create a low-key, Escherian epic. The viewer alternates between the first and third person viewpoints of a stoic traveler dressed in raincoat and pork-pie hat—a Buster Keaton trapped in a greyscale void whose landmarks consist largely of giant arrows and dimensional puns. Freissinier uses Mathieu’s stark line drawings to morph reality on the fly: barriers become doorways, outlines become as towering and navigable as China’s Great Wall, the ground destabilizes, fracturing into ice flows of direction indicators pointing nowhere. It’s like an existential Porky in Wackyland, but instead of being greeted by hordes of merry, maniacal ‘toons, the surrealism is nuanced and—set in a limitless, VR expanse—strangely compelling. Among the experiences I’ve indulged in in these past six months, this is one I keep coming back to, tantalized by its spare imagery and inventive design.

Doubling down on S•E•N•S‘s perceptual recursions, Tender Claws’ interactive Virtual Virtual Reality (2017 – OG, OR, OQ, HV, PS, GD) takes a metatextual scalpel to the whole idea of virtual escapism. Hired as human assistant to the well-heeled subscribers of a virtual reality network, you don in-game VR headsets to enter their worlds, using a hand-held grabber—not unlike the Go’s controller—to help the clients fulfill their own, um, distinctive interests. A talking stick of butter wants you to hurl endless slices of toast at it; a tumbleweed tasks you to blow it across a continually rolling treadmill, etc. Even before you are contacted by a mysterious underground seeking to take down the system, VVR goads you to anarchy—a sailboat will drone on endlessly about the beauty of the setting sun until you finally grab hold of the descending orb and begin slinging it around like a rebellious infant demigod, to the satisfyingly aggrieved protests of the water craft. Once the rebels equip you with a device that allows you to strip away the virtual facades to reveal the system’s infrastructure, the game attains a nesting doll complexity, with faux-realities unveiled, Inception-like, within faux-realities, and the vast backstage of the VR network exposed as a labyrinth of massive support structures (complete with soaring flocks of airborne VR visors), claustrophobic storage rooms, and a game room where robots play ping-pong. (Yes. Ping-pong.)

In the context of this article, Virtual Virtual Reality is one of the more challenging experiences to get through—its final boss battle is so difficult, at least for this non-gamer, that it appears the developers felt honor-bound to add a back-door to a “happy” ending that otherwise could not be reached without the reflexes of a panther. Most of the puzzles do not pose a steep challenge, though, and the wit with which Tender Claws has envisioned this worst-case scenario of tech-assisted reality denial (and bonus points for envisioning fetishism without relying on the hoary old clichés) makes the journey worth the exertion.

Virtual Virtual Reality posits a future where, if you have resources enough, you can live forever in whatever scenario you wish to be immersed. Its critique is predicated on a largely automatic assumption for VR: That whatever tale is being told, the viewer, by the nature of being plunged into the midst of the narrative, will also assume the viewpoint of its protagonist. As seen in the examples above, that does not need to be so, and in such cases as the delicately modeled puzzle game EqqO (2019 – OG; HV; GD)—where you play a mother literally watching over and guiding your blind son as he embarks on a mythical quest—the goddess-like perspective and miniature settings lend considerably toward viscerally comprehending the vulnerability of the child, understanding your responsibility in steering him safely, and ultimately realizing that, eventually, every parent needs to let go.

Nevertheless, the VR catalog is crowded with titles that make you (yes, YOU) the center of the show—sometimes to a very telling fault: Distinct among all media, VR puts a premium on isolation. Movies can be seen in theaters, music can be heard in clubs, art can hang in galleries, even books can be read out loud. But when you put on a headset, the world goes away, including whoever might be sitting next to you. Oculus (reminder: owned by Facebook) has tried to counter this by making social networking a prominent feature of the Go—ads for the device have featured celebrities interacting with each other from different locations while playing games or watching movies (no doubt in their virtual ski chalets). Looks great on TV; in practice, the jury is still out.

Some designers seek to make such isolation a virtue, largely through horror-themed experiences. Makes sense—a feeling of isolation and vulnerability goes a long way toward selling the experience of exploring a decaying, gothic mansion or an abandoned hospital. But this is the low-hanging fruit of VR, and as such, pretty overplayed—if you’ve seen one decrepit operating theater whose walls rain blood, you’ve pretty much seen them all.

Brazilian VR boutique Black River Studios takes a different tack to their audience’s sense of isolation. In Angest (2017 – OG), you play Valentina, a Russian cosmonaut slowly going mad on your solitary, and vaguely defined, space mission. Designer Klos Cunha establishes the tedium aboard a vividly conceived, Sixties-ish retro-future spacecraft—the day-to-day grind consisting mostly of tending to a hydroponics garden and undergoing ominous psychological tests (look down and you’ll discover you’re shackled to the “examination” chair)—all presided over by a condescendingly gaslighting AI. There are surreal, anxious dream sequences to portray your shredding psyche and an intriguing use of a kind of narrative ellipsis to keep the monotony from getting too monotonous—at one point you rouse in the hydroponics unit incongruously holding a wrench, only to discover later that one of the AI terminals has had its screen smashed in. If one of the overall gripes about first-person perspective in storytelling is that you can only know what the protagonist knows, Angest makes the purported limitation an absolute plus.

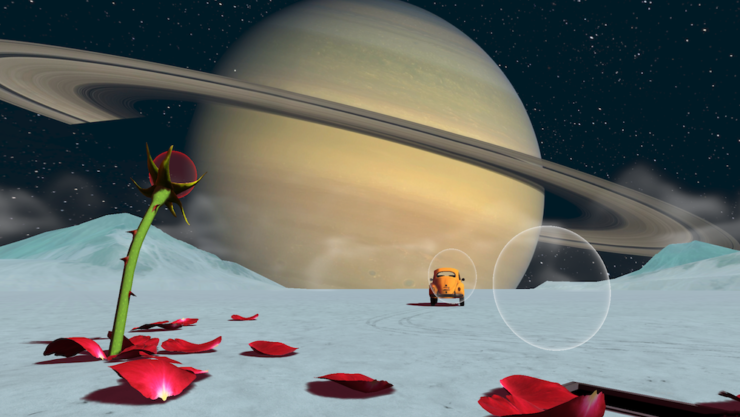

Spanish designer Carlos Coronado elevates such isolation to a whole other spiritual plane in his Annie Amber (2016 – OG; OR; ST). Tracing the life of the titular protagonist from cradle to grave, you float through a mammoth space station, traverse planetary surfaces, and embark on EVAs, each metaphorical sojourn representing a different stage of Annie’s very earthbound life—youthful rebellion; adult success; inevitable demise. It’s the human drama as space odyssey: a tale told in isolation, with nary a soul in sight. Coronado weaves his narrative by employing key settings—a beach house, a camping site—and such signifying artifacts as LP records and architectural designs (the details are so specific that you have to wonder if he might be telling the story of a specific person), while the vast infrastructure of the station, stunning planetscapes, one of the most beautiful soundtracks in the medium, and a finale both devastating and triumphant succeed in placing the life of one human on a cosmic scale. With a keen eye and profound empathy, Coronado manages to turn mise en scene into narrative, and makes Annie Amber one of VR’s most powerful emotional experiences.

***

If your passion is delving into the hows and whys of the art and science of visual storytelling, the likes of Annie Amber, Virtual Virtual Reality, and even Knives represent VR’s killer apps, those titles that not only are must-sees to appreciate the potential of the medium, but that also inspire you to hang around and explore more, to see where things go. But beyond that, their advent from outside the world of corporate entertainment demonstrates that a culture eager to test and nurture the promise of VR exists and is growing. It is not dissimilar to the cinema of the ’70s, when auteurs like Altman, Scorsese, and Ashby were rising out of the ashes of old Hollywood, with their own voices and new, some would say radical, approaches to storytelling.

And to further stretch an already strained metaphor, what Star Wars was to the independent spirit of ’70s cinema—in other words, the thing that cut off a still-in-progress rebirth by showing the corporate side a new way to print money—the recently released Vader Immortal (initially only for the Oculus Quest and Rift S) may be for the inventive laboratory that VR has so far been. Okay, that’s a bit apocalyptic—one thing VR has now that movies didn’t fifty years ago are online stores that give independent creators equal access to audiences. Even with the incursion of one of the biggest franchises in film history, there are positive signs that creators will find their own reasons to continue exploring and inventing.

The inroads are plentiful enough—and maybe, in this case, history won’t repeat in quite the same way.

Dan Persons has been knocking about the genre media beat for, oh, a good handful of years, now. He’s presently house critic for the radio show Hour of the Wolf on WBAI 99.5FM in New York, and previously was editor of Cinefantastique and Animefantastique, as well as producer of news updates for The Monster Channel. He is also founder of Anime Philadelphia, a program to encourage theatrical screenings of Japanese animation. And you should taste his One Alarm Chili! Wow!